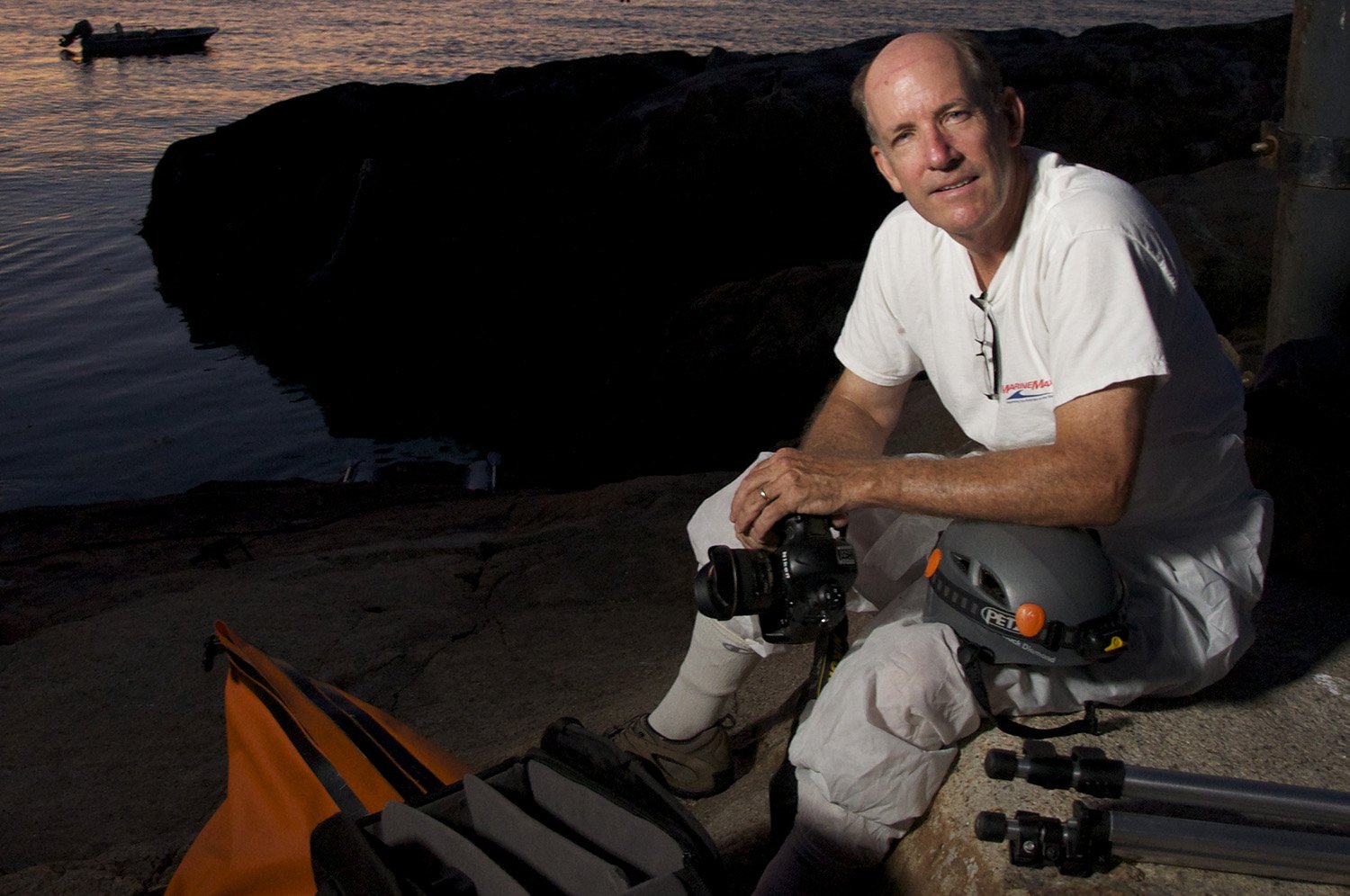

For more than 40 years, David Zapatka has been a television cameraman working primarily at the network level for news and sports programs. He got his photographic start as a 13-year old with his first camera, and with this portfolio, returns to those roots.

His night lighthouse photographic project was adopted in 2018 by the United States Lighthouse Society and is called USA Stars & Lights. As of the summer 2022, he’s visited 19 states and has similarly captured more than 190 lighthouses at night under star-filled skies during new moon phase when nights are darkest. His latest book USA Stars & Lights: Portraits from the Dark was published by the USLHS in 2020, and sales proceeds support USA Stars & Lights travels.

Thank you for visiting and supporting this project!

Frequently Asked Questions

-

I get asked this all the time. Yes, it’s a picture of a lighthouse. And yes, there are millions of lighthouse pictures, but of all those taken throughout 160 years of photographic history since being invented in 1857, you find few lighthouse photographs from nighttime. Why? Because film could not do the kind of work today’s digital cameras can achieve. Plus, for the first two hundred years of lighthouses in America, most were on fenced properties. Now, with the federal government turning them over to local governments, foundations, or private owners, they have become more accessible to the general public. Combined with the new camera technology, nighttime photography is a growing genre. But for many locations, I spend hours researching ownership, securing permission to visit at night, and in some cases, researching and planning logistics to reach lighthouses normally inaccessible, often times by boat. Once I’ve arrived on location, the easy part, the photography, begins.

-

All photographs are single images and are achieved in the field. I don’t use Photoshop, but I do adjustments of every image in Lightroom, another Adobe software product similar to Photoshop. But I have never added stars to any photograph, and what is on the final print is often what I see while on location. The light waves hitting the digital sensor are known as latent images, and on location I consider the entire scene before me to be the pallet. I take careful stock of what is before me, and most always light the scene with battery powered LED instruments set in strategic spots. Since the exposures are relatively long, at most 20 seconds long, the lights are usually dimmed down to their lowest level. A little light goes a long way, and an open shutter for 20 seconds is an eternity in photography. I’m essentially exposing to capture the best dark sky and loaded star field that happens to have a beautiful lighthouse in the foreground. I also have to worry about the brightness of the beam, but I use a very good camera to help with that issue. The hardest lighthouses to shoot are those with beams constantly on or powered through magnificent Fresnel lenses. Those are challenges I often encounter when arriving at locations. Remember, night photographs of lighthouses are rare, and often times I’m the first to ever capture them in this way. There are usually no night reference photographs to research before arriving on any location.

-

What concerns me the most is certainly my personal safety. Whenever possible, I have an assistant along to help. But that’s not always the case, and often times I find myself alone in the dark. Being able to do a daytime land survey of a location often adds to a safe shoot, but it’s not always possible to do before arriving at a lighthouse location. I always have a bunch of personal safety equipment with: a rock-climbing helmet with headlamp; a personal flotation device (PFD) with a satellite transponder known as an IPIRB in my pocket; and in the camera bag are ice crampons for when slick seaside rocks are encountered. I always let loved ones know of my plans as well as local police or the Coast Guard. Many times, foundations or private owners are on hand to help or simply to observe me as I work. Many find it fascinating what the camera can achieve, and most have never had their lighthouse photographed in this way.

-

I often have other photographers joining in on lighthouse shoots. Some are there to simply watch the process play out, others are there to assist. Some will arrive with expensive new cameras with 42 million pixels. Because a camera has that much resolution does not mean it is the best tool for night photography. I happen to use a 10-year old Nikon D4 for most of my shoots. It has 14 million pixels, but it remains one of the best cameras ever made for nighttime photographs. I’ve been asked about the newer mirrorless cameras, but have yet to invest in any. The D4 has served me really well, and as mine gets older, I’ll have to either get another used one, or start thinking about going mirrorless. Having the best and fastest lens possible is really important. A fast lens means it allows for the widest iris opening possible. Many “kit” lenses that come with consumer-level cameras are not particularly good for night photography. Investing in “good glass” is important to achieving nice nighttime images. Most of my photography is achieved with a 14mm f2.8 Nikkor lens. Photography is all about working with light, and I’ve got 40 years of television experience I bring to each lighthouse. One badly placed light can ruin a shoot, especially if it is placed too close to the camera. For me, I love being able to create not only light, but to also create well-placed shadows within the scene. That’s where the art comes from.

-

I’ve a long history of donating my time, going back to my teenage years as a volunteer firefighter. I’m getting close to 200 lighthouses captured at night, and that’s only ¼ of those still functioning in the country. If I can get this project funded—and it’s a part of the nonprofit United States Lighthouse Society—then I’ll continue traveling and shooting as long as possible and until most have been photographed while working deep into the night.

July 2022 feature on The Today Show